Nikon 28-80mm v Nikon 28-85mm v Nikon 28-105mm v Nikon 35-70mm

With photographers abandoning bijou mirrorless systems for full frame SLRs, May 2020 feels like a great time to review the walkabout lenses of another century. Bored by the low-hanging fruit of optically faultless 24-120mm kit lenses, today’s image-makers crave the creativity-testing limits of zooms with fewer focal lengths and the coveted ‘vintage look’ of badly corrected wide apertures. Perfect is too easy. Weary of sharp, pocketable lenses with in-built stabilisation and greased lightning autofocus, proper lensmen want massive, gritty manual-focusing zooms that take as long to AF as it does a bird to fly out of frame and arrive at a distant migration site – with implausible macro modes and stabilised by sheer inertia. Like their dads. The lens, that is – the lenses are stable because they are heavy – not their dads. They’re heavy too, but not always stable. In fact, often less stable because of muscular atrophy and inner ear issues – a bit like sensor stabilisation gradually breaking down. I’m drifting . . .

Let’s be honest: the appeal of old school zooms doesn’t lie in their (unwarranted) reputation for extreme sharpness, or their (very-much-warranted) reputation for bettering agar jelly as a fungal medium. It may pertain to their ‘thingness’: the unalloyed joy of handling well-wrought machinery. But let’s be really honest: if it there was a run on old Nikon glass, it would be driven by price. Which would drive prices up. Right now no-one wants these old clunkers – which makes them all the more appealing to those who follow the mantra: “everyone else is doing it, why should we?”

The 1990s was the era of the 28mm walkabout zoom. At the long end you might tiptoe into portrait territory – but generally the rule was quality or quantity. Some relics from the 80’s – the era of 35mm walkabout zooms – survived to remind buyers that constraining the focal range reaped optical benefits: lenses like the Contax Zeiss 35-70mm f3.4 (little more than a 50mm with benefits) handily outperformed primes in their range. Nikon’s version was faster and rightly considered a benchmark for mechanical and optical excellence. But was it better than the well-regarded 28mm zooms? How does it compare to today’s lenses? And How well does it work on a Speedbooster for Sony NEX or M43?

Hmmm. At some point, Nikonistas have eulogised most of the 28mm zooms as the cat’s pyjamas. I’m not going to repeat well-worn factfiles but by way of introduction I will say this:

• The plastic fantastic 28-80mm f3.3-5.6 weighs almost nothing and is commonly considered to be Nikon’s best value lens ever.

• The 28-85mm f3.5-4.5 AF-n weighs more than some modern cameras and is also much loved. Although the barrel is metal, the focus and zoom rings are plastic and a bit rattly. Perversely it has a macro setting that only operates at the wide end.

• The reassuringly chunky 28-105mm also has a wilfully odd macro mode: 50-105mm with a working distance of 12mm from the front element – at which point it has a best ratio of about 1:2. Why? Just, why?

• The 35-70mm f2.8 is the lens you want to document a war with. Not only is it bomb-proof but it operates like a pump-action shotgun.

If I had pretensions of being a proper journalist I would Google what these lenses cost new, the year of their release, weight, elements and groups and all that. Maybe it’s the coronavirus talking, but I really don’t care. Here’s the bottom line:

• Nikon 28-80mm f3.3-5.6: £39 from London (eBay)

• Nikon 28-85mm f3.5-4.5 AF-n: £57.22 from Bad Zwischenahn (eBay)

• Nikon 28-105: £105.07 from Tokyo (eBay)

• Nikon 35-70mm f2.8: £139 from Glasgow (eBay)

Careful shopping yielded a crop of lenses in great condition, free of fungus, balsam separation, oily diaphragms or haze. They’re share the same price bracket: almost free. But we can compare them elsewise . . .

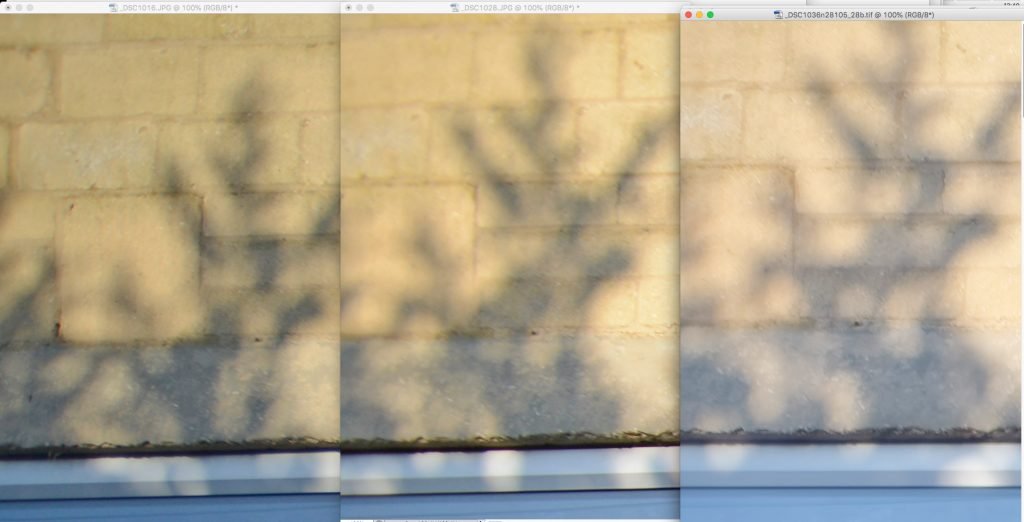

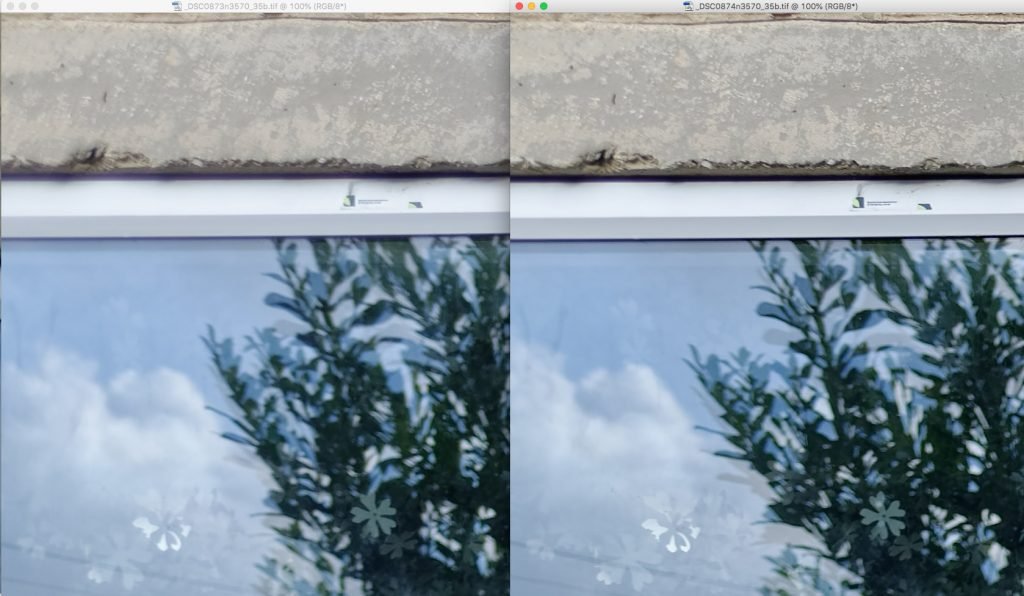

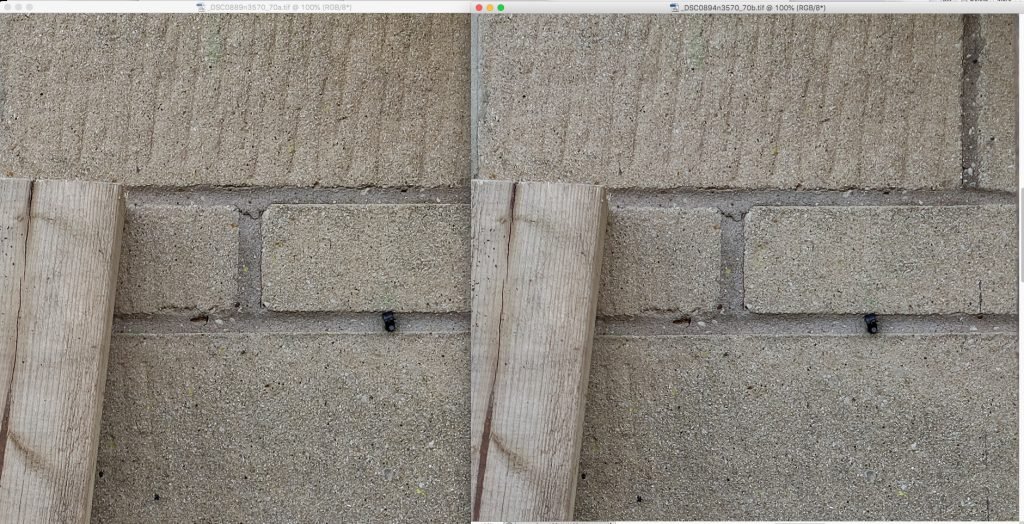

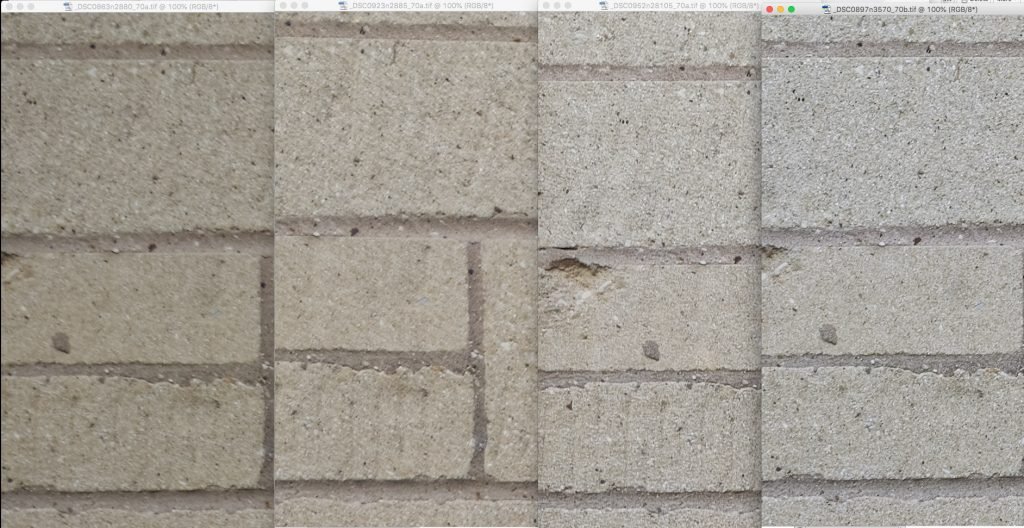

Sharpness at 28mm

The flimsy 28-80mm is a hair sharper and faster than the 28-85mm wide open. However, the 28-105mm has the unfair advantage of being supported by a fully-fledged DXO profile, and when we play this card, we see it’s the best of the bunch. Each gives a thoroughly serviceable capture wide open in the centre frame. Whereas in the corner…

No amount of profiling can disguise the fact that the humble 28-80mm serves up the least terrible corners at f3.3. However, it suffers the worst field curvature and barrel distortion at this focal length. To their credit, none of these lenses suffers from conspicuous chromatic aberration. On the far right, the 28-105mm gets its vignetting and geometry corrected courtesy of DXO. I’m reluctant to call any of this useable, though – and this in the neighborhood of f4, mind you. Until quite recently, sharp corners at wide angles and wide apertures was a big ask; for a 28mm zoom lens in the 90s it was too big an ask. Stopping down, though . . .

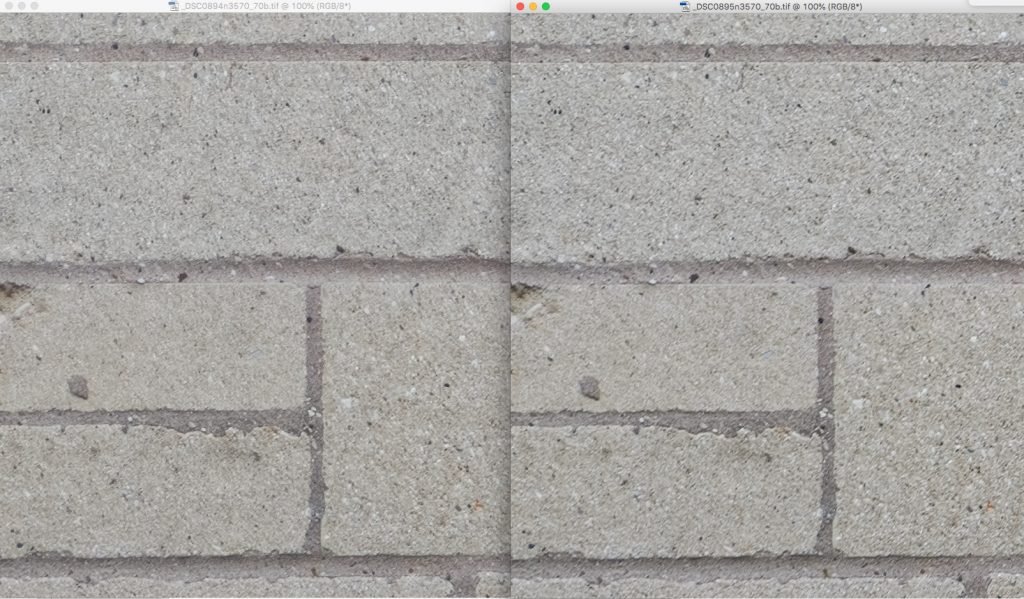

Sharpness at 28mm / f5.6

The profiled 28-105mm offers a credibly resolved Zone 1 at f5.6: nothing to complain about. The 28-85mm has improved to a greater degree than the 28-80mm which is still obviously soft.

However, the unlikely 28-80mm holds onto Zone 3 (in the extreme corner) better than any of this group: out here, at this focal length, the 28-85mm really wilts. Stopping down further to the most old school focal length of all . . .

Remember the old days when you had to stop a lens down to f8 to get a useable corner? The 28-105mm here finally delivers a pleasing Zone 3, with DXO assistance. The 28-85mm retains an advantage over the 28-80mm across most of the frame, but still looks uncomfortable in the extreme corner compared to the plastic pretender whose rendition is commendably consistent.

But do you remember the really old days when a lens didn’t hit its stride until f11? Nothing has significantly changed here since f8, except an improvement in the corners. By corners we here mean Zone 3: the outermost part of a full-frame image circle – in this case, of a 36MP Nikon D800E – itself a relic now, but barely less demanding than the current state-of-the-art.

There’s little point in showing f16, because it’s inevitably a slightly softer f11. Twas ever thus. The pecking order remains in line with the pricetags.

At this juncture we ponder progress: a contemporary alternative like the Sigma 28mm f1.4 is a world apart, optically, from these designs – at wide apertures. In Zone 1, it’s sharper at f1.4 than these are at f5.6. At f2, its Zone 3 is better than anything these oldsters can muster. But if you’re actually shooting at f11, at middle distance, a Nikon classic like the Nikon 28mm f2.8 AIS is barely distinguishable from today’s best. Similarly the 28-105mm at 28mm / f11 turns in a fully pro-grade capture. It remains true that you pay for wide aperture performance – but if you don’t need it, you don’t need to pay for it.

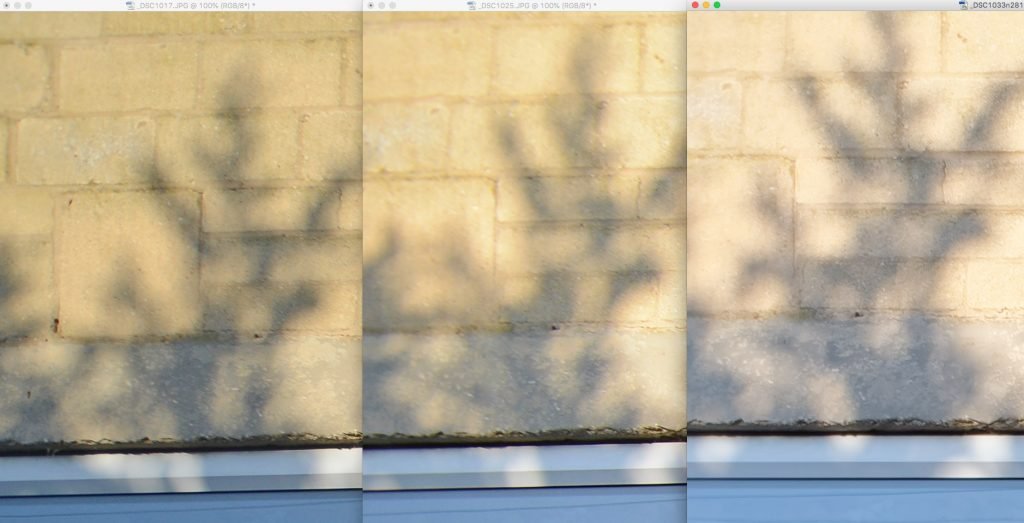

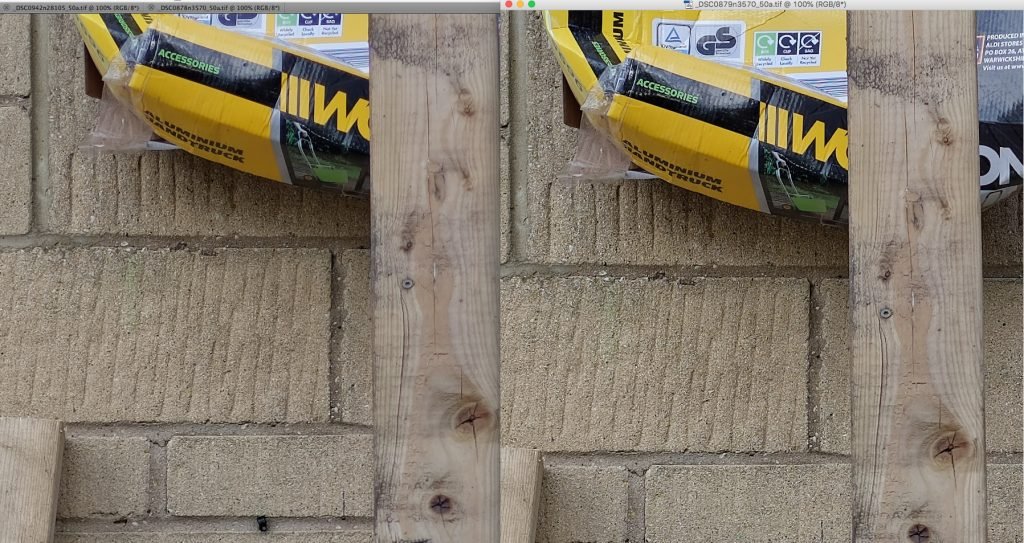

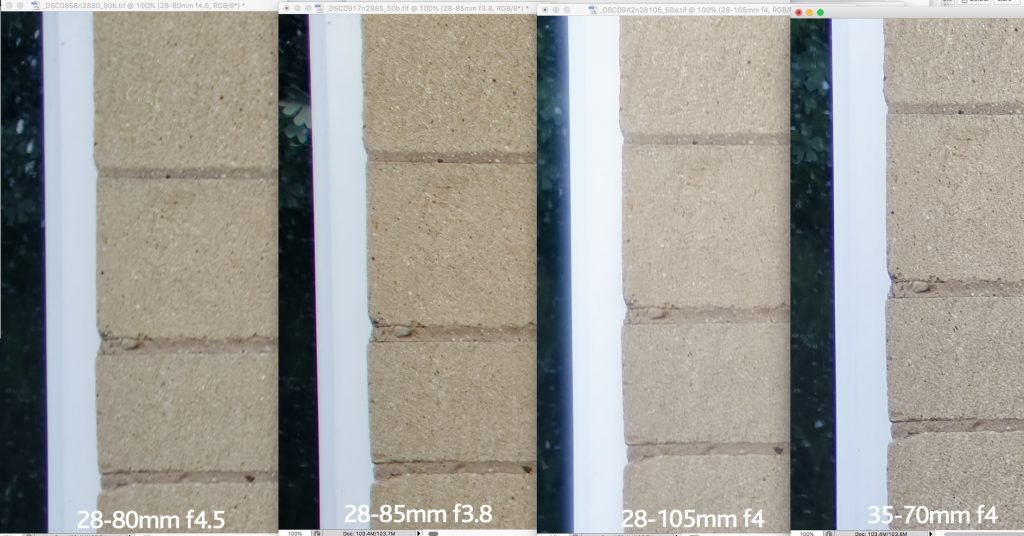

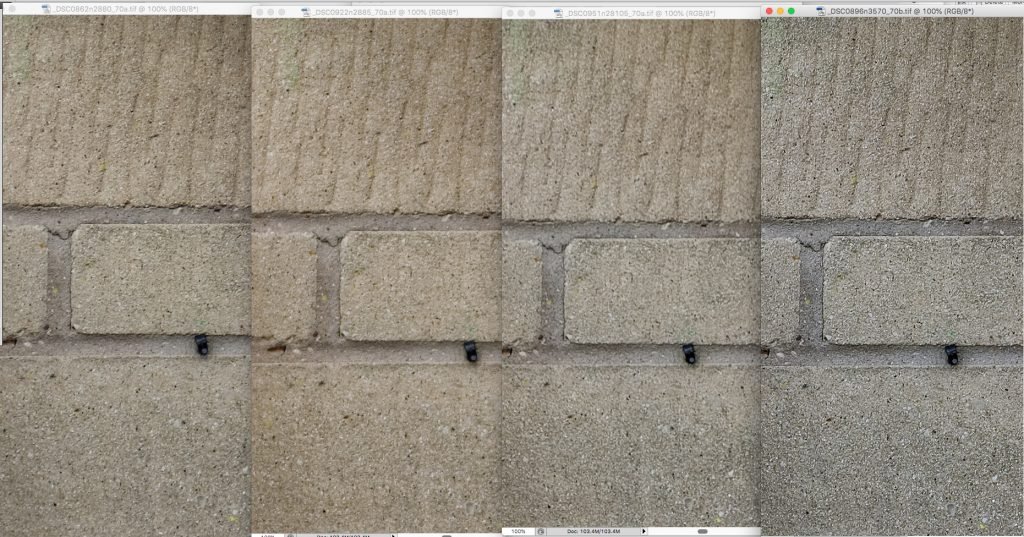

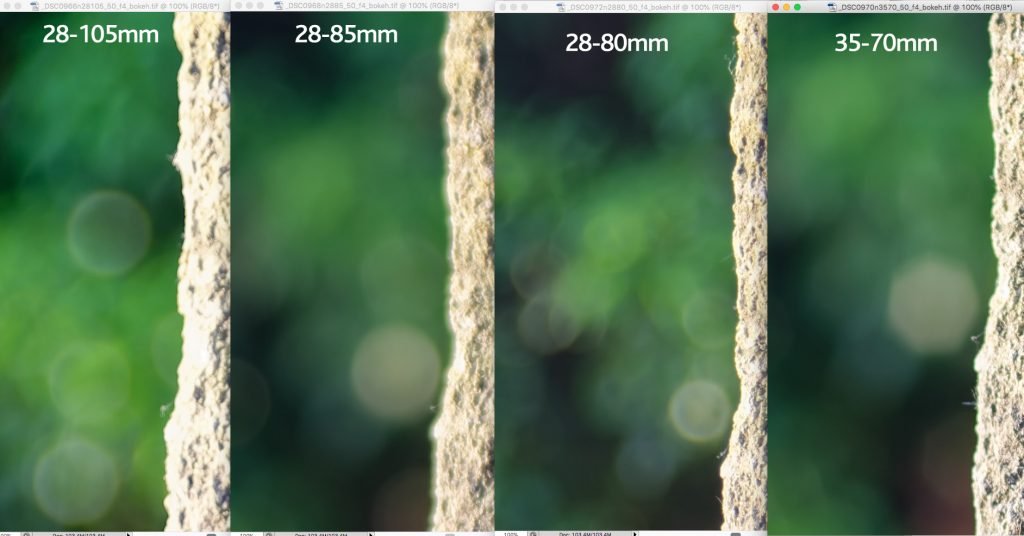

Sharpness at 35mm

Here, the 35-70mm f2.8 joins the group to show how it’s done. It too benefits from having a DXO profile for Nikon full frame. Let’s see how this blunderbuss looks wide open and one stop down:

Zone 1: great at every aperture. Zone 2: just presentable wide open; excellent at f4. Zone 3: not critically sharp wide open, but thoroughly useable at f4. Broadly, this is similar to a top-flight modern zoom. The main difference is that a bulkier Nikon, Sigma Art or Tamron 24-70mm f2.8 will do it down to 24mm with image stabilisation.

You’ll see from the following that the 35-70mm f2.8 is in a different league to the 28mm zooms, although at smaller apertures the 28-105mm runs it commendably close.

Again we see that the 28-80mm, despite being outresolved by its elder siblings in Zone 1 (centre), has a remarkably tidy Zone 3 (corners) at its maximum aperture of f3.8 / 35mm. Centre-frame, the 28-85mm and 28-105mm are too close to call, but the 28-105mm needs further stopping down to be serviceable.

At an aperture modern lenses are flying, these old-timers are just waking up. Again the 35-70mm is clearly superior and the 28-80mm clearly inferior centre-frame, with the others hard to separate. However, close inspection of the outer image circle reveals differences: the 28-85mm gives us the only slight manifestation of CA, and across most of Zone 2 higher resolution, along with higher aberration. However, it fades badly in Zone 3 compared to the 28-105mm which behaves consistently across the frame by f5.6 – though its performance isn’t as even as the 28-80mm which continues to impress with aberration free corners.

The story of f8-11 is that of the 28-105mm stepping up and away from the 28-80mm and 28-85mm and almost, but not quite, reaching the level of the 35-70mm.

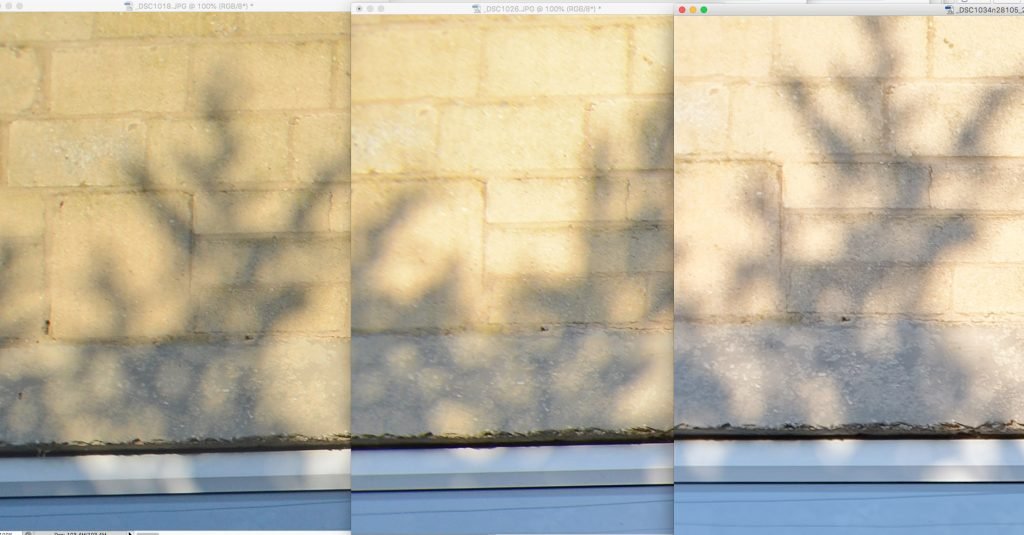

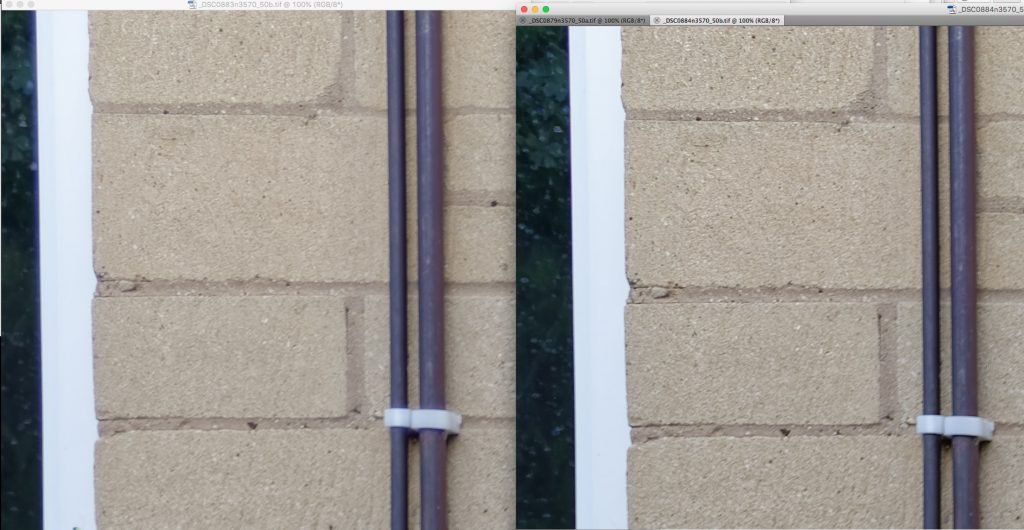

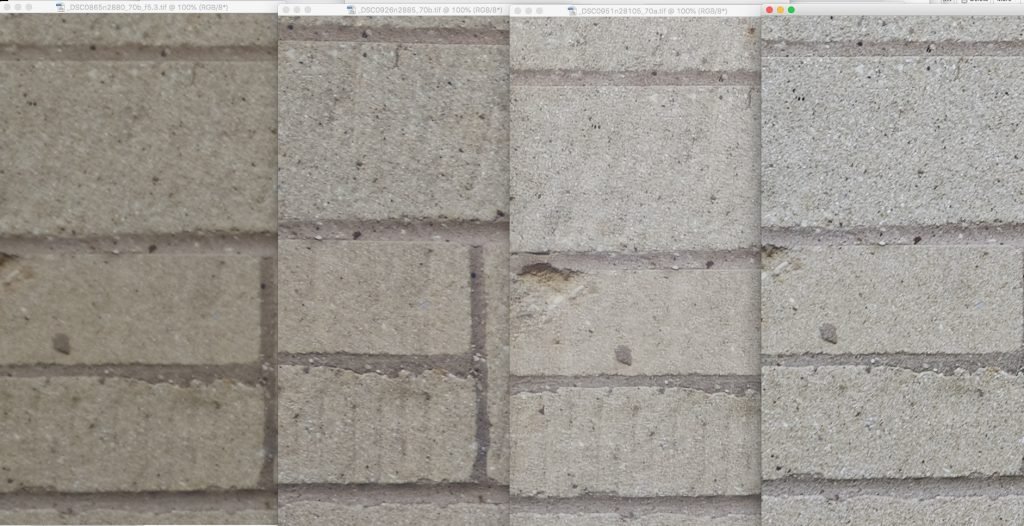

Sharpness at 50mm

At 50mm the Nikon 35-70mm is perhaps slightly keener at f2.8 than at 35mm, but as before, it’s very good wide open and superb at f4.

At 50mm it’s the turn of the 28-85mm to be second best across the frame. The 28-105mm has conspicuous spherical aberration wide open in Zone 3.

Stopping down from f5.6-11 at 50mm, we see the same step up in performance at f8 from the 28-105mm, but whereas at 35mm it pulled well clear of the 28-85mm, at 50mm the 28-85mm delivers the best Zone 3 apart from the 35-70mm, although away from extreme corners, the 28-105mm is still sharper across the frame. The 28-80mm plods along benignly and vicelessly in last place, delivering consistently almost-adequate results at every aperture, zone and focal length.

Sharpness at 70mm

There’s so little difference between wide open and f4 that we should consider 70mm the peak focal length of the 35-70mm f2.8: performance improves steadily as you zoom in: here it is exceptional.

By 70mm, f4 is beyond the capability of the 28-80mm. Reprising the pattern of shorter focal lengths, the 28-85mm is sharper across the frame wide open, but neither approach what the 35-70mm can do.

70mm repeats the pattern of 35mm: from f5.6 through to f11 the 28-105mm pulls ahead of the shorter zooms and genuinely matches the 35-70mm f2.8 by f8. Impressive.

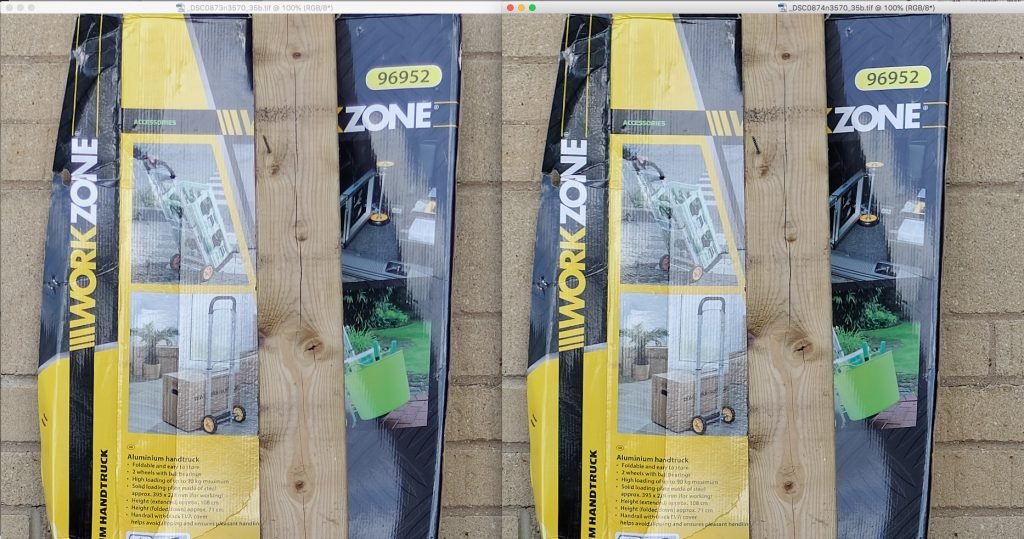

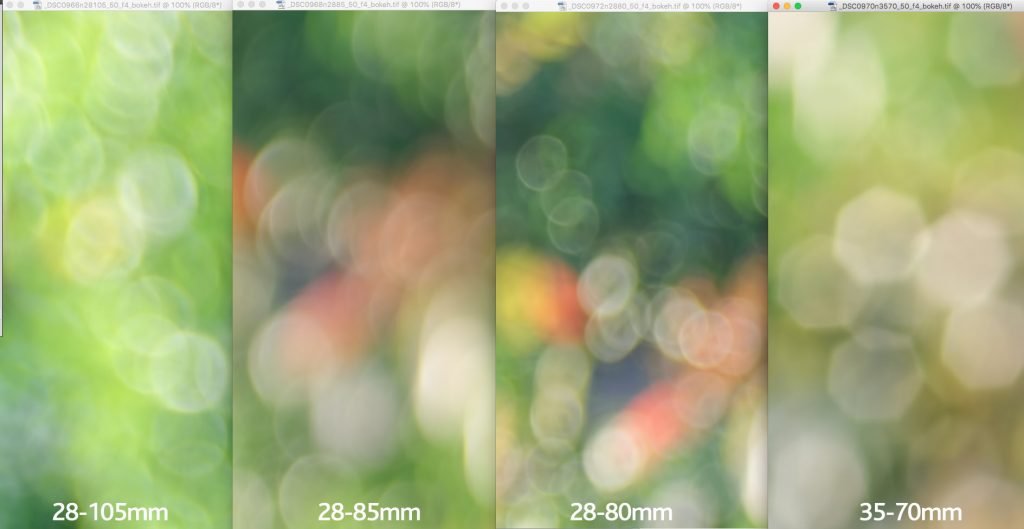

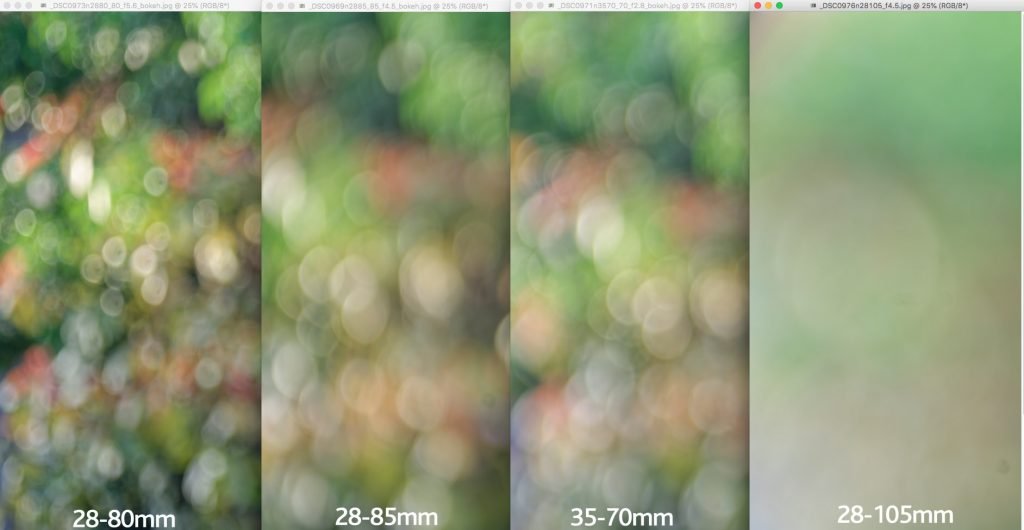

Bokeh Tests

Here, a typical scene of highlit foliage was shot with each lens at 50mm f4.

No doubt the 28-85mm produces the most harmonious bokeh, closely followed by the 28-105mm – both quite good for zoom lenses. The 35-70mm’s heptagonal highlights are distinctive and ugly. Or is it retro? The 28-80mm is compromised in quality and quantity: the aperture shape is deformed; there are strongly pronounced edges and scruffy inner figuring. The 28-85mm bokeh balls smoothly transition into their background – almost like Olympus ‘feather bokeh’: they’re neutral-to-soft. Also, bokeh balls retain more of a circular shape as they move into Zone 2 and 3. Backgrounds shot with the 28-105mm are slightly more nervous because of some edge highlighting, but internally bokeh balls are smooth. Overall it’s tidy – a worthy second place.

However, the near-focus test scene (60cm) showed up a significant close-range correction problem with the 28-85mm that the middle-distance resolution tests hadn’t revealed.

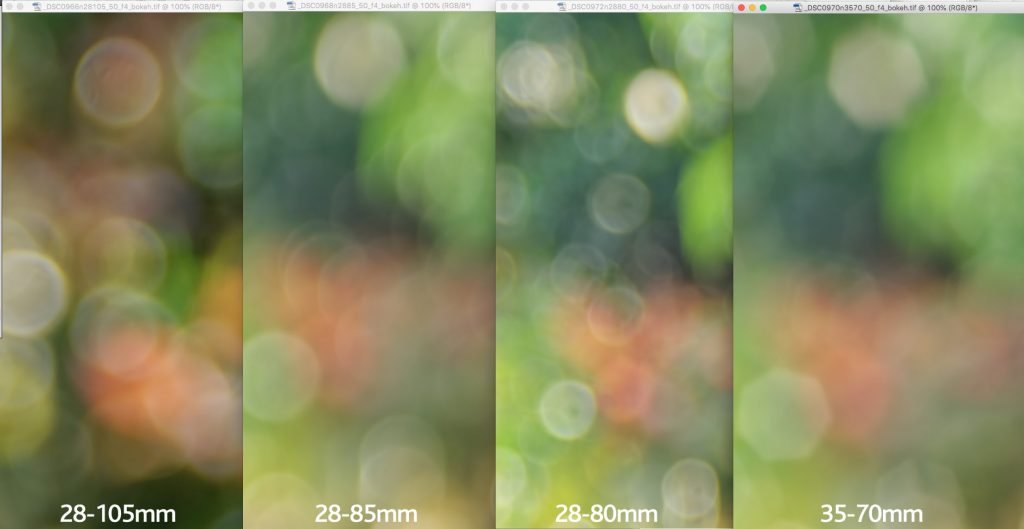

Next, at the same test scene, each lens undertook the ‘Bokeh-Max’ challenge: deploy its optimal combination of close focus, focal length and wide aperture to give maximum background isolation.

The 28-80mm cements its last-place position with a not okay bokeh-inducing 80mm / f5.6 at a minimum focal length of 35cm – scoring low for quantity and quality. Backgrounds tend to be uniformly busy and distracting with this lens.

Note that the subject-isolating power of 70mm f2.8 is comparable to 85mm f4.5. However, wide open, the 35-70mm hides its ugly aperture and produces better regulated bokeh balls that are almost as smooth as the 28-85mm at a smaller aperture. Bokeh here is good.

However, for sheer scenery-obliterating prowess, the 28-105mm demonstrates the benefit of getting up close – and that when subject isolation is needed, a longer focal length is more effective than a wider aperture – and cheaper, too. Much fun can be had with this lens.

Light Handling

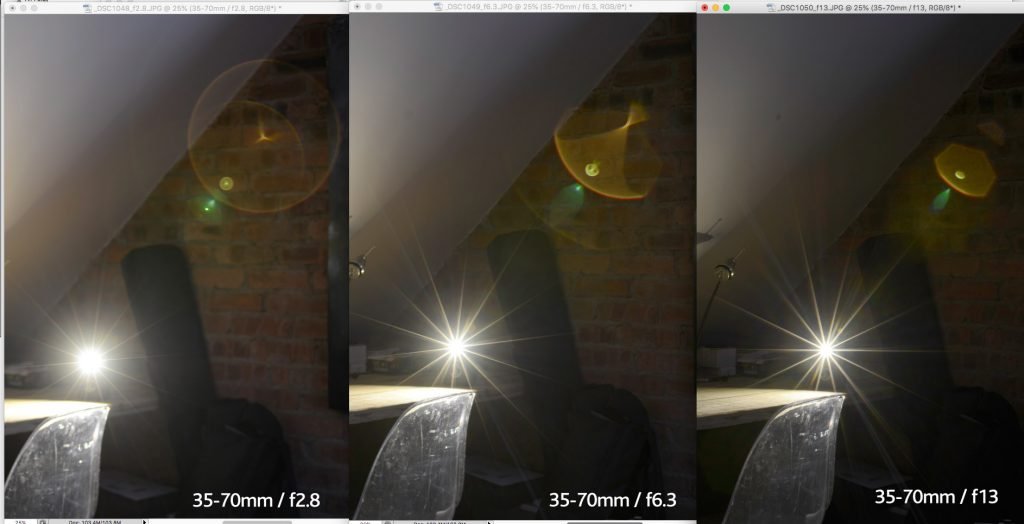

Shining a strong light contrawise against the front element in order to provoke maximum ghosting and flaring gave the following results:

At one extreme the Nikon 28-80mm has no ghosting at all, but renders point light sources with massive halation. At the other extreme, the Nikon 35-70mm has flagrantly excitable ghosting issues, but beautifully controlled sunstars (hoshi). That raking axial string of ghosts is practically an exploded diagram of its components. In between, the 28-105mm has better control over internal reflections, but like the 28-85mm can be provoked into funky flaring.

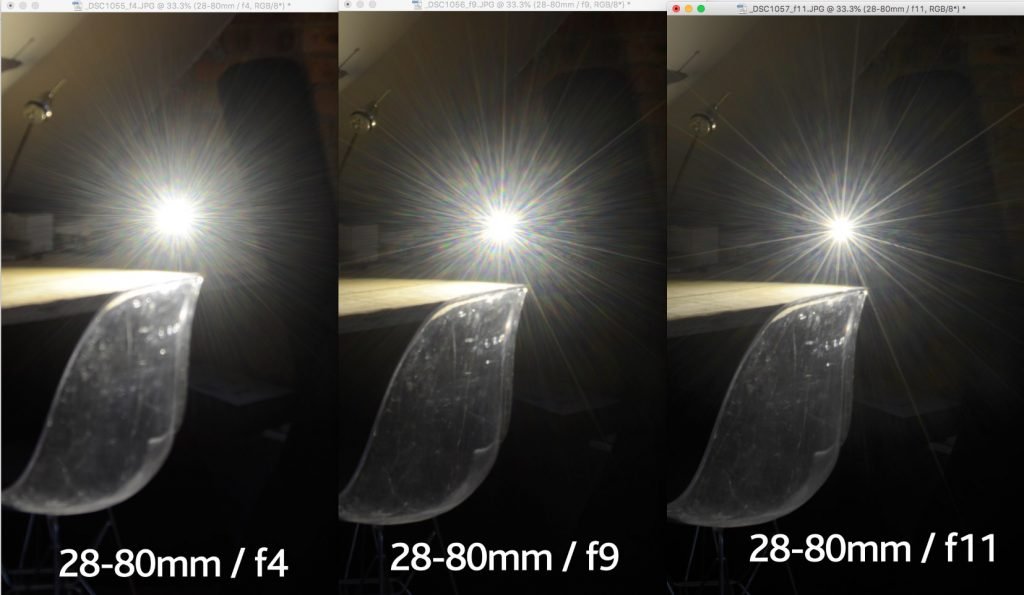

Sunstars

The 28-80’s policy on sunstars is “No”. From f11-16, a strangulated sea-urchin of a thing can be made of point light sources, but this isn’t a lens for elegant night scenes. On the upside: no ghosts.

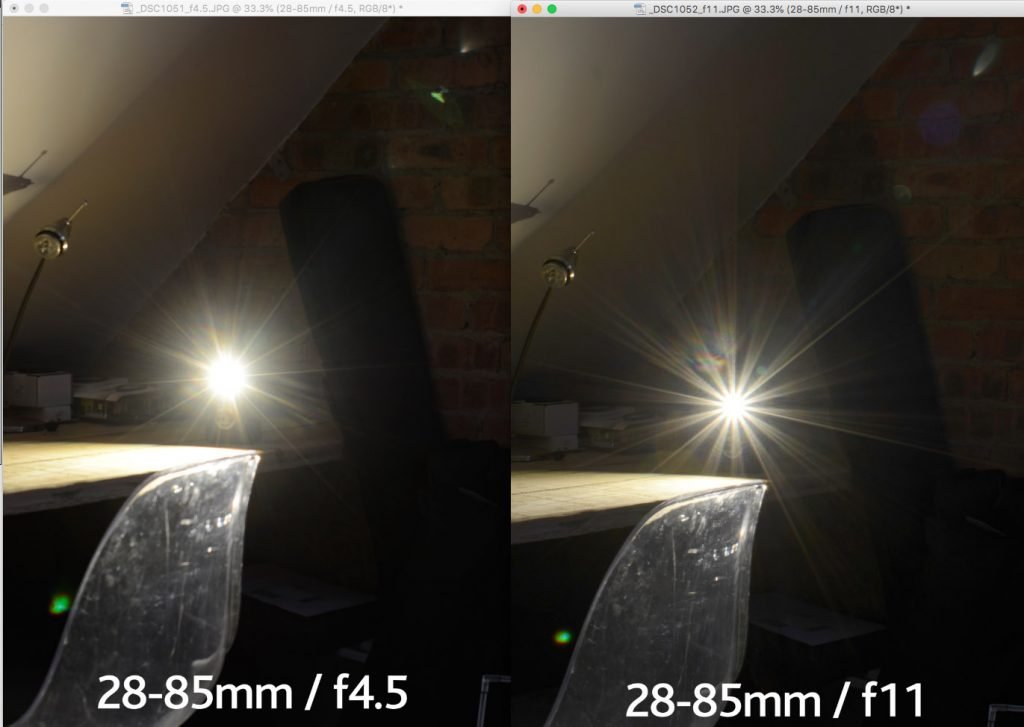

The Nikon 28-85mm is also reluctant to get starry: there are multi-coloured artefacts at all apertures and light sources are badly handled, with mushy halation. At f11, a poorly defined double-spoked 14-point star appears.

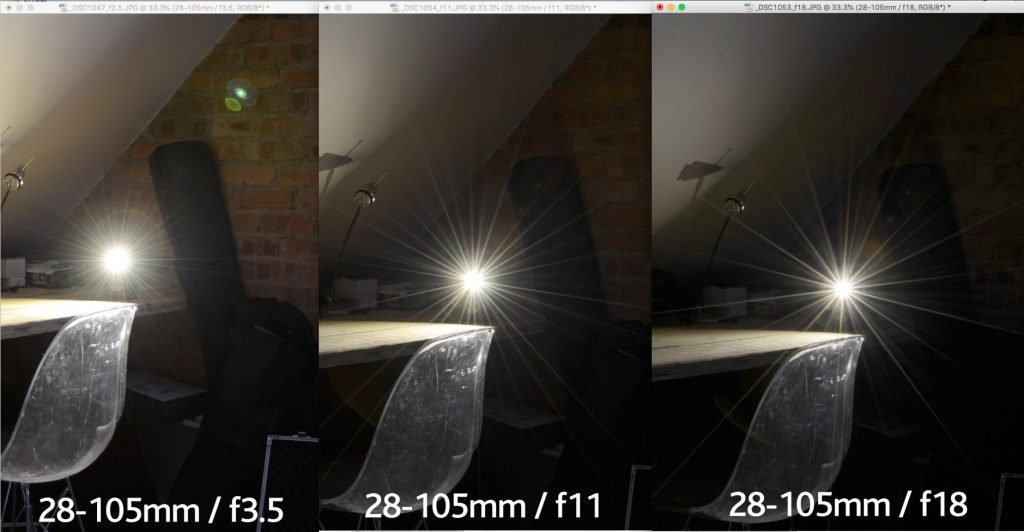

The Nikon 28-105mm draws stars more like a prime. Only wide open is there some ghosting. Although light sources at wide apertures have some halation, there are also attractive radial figures that mature into slender Zeiss-style converging stars. The eight-blade aperture produces 16 spokes but they are shadow-doubled in an attractive way, with paler 16-spoke rings at the rear, giving the impression of 32-point stars.

There’s a place for lens flare. Personally, I’m not sold on anamorphic flare that enjoyed its moment in (and around) the sun a few years ago. This is much prettier. Perhaps some day an enterprising film-maker will shoot a sci-fi blockbuster with the Nikon 35-70mm f2.8 – because without even trying, it turned a corner of my studio into 2001 – A Lens Oddity. Arri-like stars, average veiling, outrageous ghosting. Such fun.

CONCLUSION

Nikon 28-80mm f4.4-5.6: Yes, it’s consistently quite sharp at all apertures, focal lengths and zones. Autofocus is the swiftest of this group. But colour rendition is flat and apart from being impressively light, cheap and relatively sharp in Zone 3 at wider apertures, there’s little to love. It doesn’t even sport a bizarre macro function that requires Aztec-level alignment skills to engage. It lacks character. I suppose it makes as much sense now as it ever did as a first, dependable, kit lens you’re not afraid to damage. Meh.

Nikon 28-85mm f3.5-4.5: While this feels like a proper lens, its existence is hard to justify when there’s the 28-105mm. Apart from slightly more refined bokeh at typical working distances, the 28-85 is a bit softer, a bit less versatile, much less useful as a macro lens, and it doesn’t handle light sources in a way that’s either grown-up or hilarious. It is cheaper, though: if your budget is strictly limited to £50 and you’re wondering whether to get this or the 28-80mm, get this every time.

Nikon 28-105mm f3.5-4.5: The problem is that it’s increasingly soft at maximum aperture as you rise through its focal range. But apart from that, it’s brilliant. Stopped down to f6.3, it’s very good at every focal length, and in the f8-f11 range it’s fantastic for the price. The macro mode is a blast, allowing shots that shouldn’t be possible, upending the defocused part of your world into a smoothie maker. It even draws nice stars. For £100, it’s a keeper.

Nikon 35-70mm f2.8: This feels like an old lens. The trombone zoom is prehistoric; the AF clatters and wheezes; it’s heavy for such a small thing – there must be some fat chunks of glass in there you could poison dissidents with. It behaves like it’s possessed when confronted with point light sources. Bokeh at f4-5.6 is like a Cubist collage. But my goodness was it ever capable of taking lovely pictures: increasingly sharp wide open as it pumps toward 70mm, without a trace of lateral CA. It’s even well corrected for geometry. This is a lens with soul, made to last, and it’s hard to part with a clean one, even if you won’t use it often.