The 28mm focal length (14mm in MFT) is the gateway to wide-angle. It’s an architectural photographer’s staple. Many lenses cover it: it’s typically at the top of a wide zoom and the low end of a standard zoom – where both tend to be weak. There are few MFT primes in this territory: Panasonic has the 15mm f1.7; Sigma has the 16mm f1.4, so we’re first examining zooms. A modest lens that delivers acceptable results is always handy – but, more importantly, it establishes a baseline for faster primes to beat.

At this point, I’m not interested in wide aperture performance or shallow DOF. I’m concentrating on a typical scenario shooting interiors, products, landscapes or exteriors, where thick DOF and maximal detail all the way to the corners is generally required.

The following comparison is the result of shooting each lens at each aperture with the G9’s 80MP High-Res mode, processed through PhotoLab using its profiles, with a strong combination of lens sharpening and USM to combat pixel-shift fuzz.

Each lens found its peak moment: the Panasonic 14-45mm f3.5-5.6 and Panasonic 7-14mm favour f5 at 14mm; the Leica 12-60mm f2.8-4.0 likes f4.5; the Nikon 14-24mm f2.8 is happiest in Zones 1/2 at 14mm at f4. It was adapted by the stock Metabones adaptor (not Speedboosted). For comparison, the Sigma 24mm f1.4 Art @ f5.6 was shot on a Nikon D810, FOV equalised and processed via PhotoLabs’ lens profile.

Breaking with tradition, I’m going to start with a rather surprising conclusion: nothing in this group can live with the blazing brilliance of the rattly old £50 Panasonic 14-45mm. Here are centre-frame 100% crops of the 14-45mm vs the other two Panasonic zooms:

|

|

|

In the centre frame, the performance delta between the older Panasonic lenses is less than that which separates them from the inferior Leica 12-60mm f2.8-4.0.

For comparison, let’s look at the centre-frame performance of the Metabones-adapted Nikon 14-24mm f2.8, and the same scene shot with the Nikon D810 and the Sigma 24mm f1.4 Art:

|

|

|

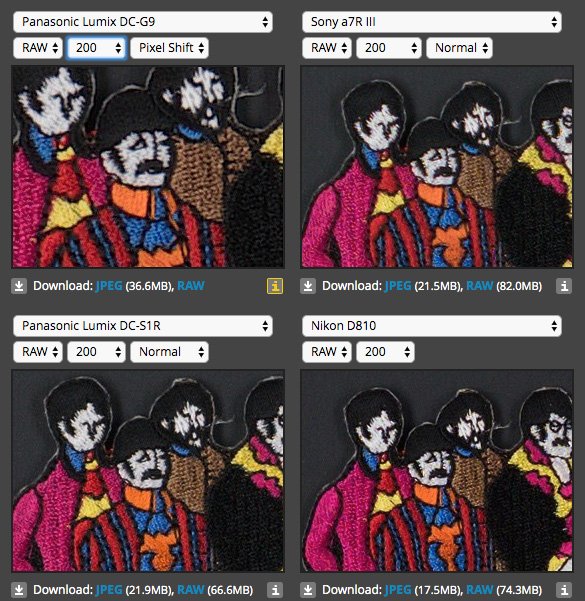

We have to say some things at this point. First, you’ll have noticed the aggressive sharpening I employ as a standard policy: in my experience, a slight oversharpening at 100% gives better-looking downsampled files and very large prints. It also better reveals the lens. Second, the adapted Nikon lens is disadvantaged by not having a PhotoLab lens profile, and has been manually sharpened and corrected. Third, the 36.3MP Nikon D810 is hardly state of the art compared to the current crop of c.50MP DSLRs. But I would contest that in terms of pure sensor performance at low ISO, the D810 is still competitive. Obviously an extra 10+MP matters, but as the following graphic shows, the difference between the D810 and the S1R is much smaller than the difference between the S1R and the pixel-shifted G9.

Fourth – damn! What is it with that nasty little 14-45? Let’s move into the mid-zone of the image circle on the same focal plane and compare more 100% crops:

|

|

|

This is progress? Leica’s brand new £700 premium zoom is trounced utterly by a £50 plastic trinket from the dark ages. To be fair – and this is a sentence I can barely believe I’m about to write – in the badlands of the image circle not even the Nikon 14-24mm f2.8 can quite live with the Panasonic 14-45mm f3.5-5.6 kit lens – although it certainly exposes the absymal outer-zone performance of the Leica f2.8-4.0 at this focal length. Sadly, this level of inadequacy is typical of many MFT optics. As the for the Nikon D810 – it doesn’t matter how good the lens is: there aren’t enough pixels to compete.

|

|

|

Moving further towards the corner on the opposite side of the frame . . .

|

|

|

How did a little lens able to do this in the extreme corners get to be so good and so obsolete? PhotoLab’s Edge Offset has gone OTT in the images below; the Nikon 14-24mm is probably resolving fractionally better in it’s full frame Zone 2, behind different sharpening regimens.

|

|

|

On any platform the Nikon 14-24mm remains a resolution benchmark. Current Otus and Sigma primes may match or exceed it’s capability, but it’s hard to absorb the idea that an ancient, tatty kit lens can take it to church in this way. It’s also difficult to come to terms with what is apparently a fact in 2019: that an £800 Lumix with a joke lens captures significantly better images at 28mm than any DSLR apart from its similarly shifty big brother, and all but the very best medium format cameras.

That shouldn’t be true. Sorry, but I need a breather while I turn my private universe inside-out to process this new intel . . . .